Hughes syndrome, also known as 'sticky blood' or 'Antiphospholipid Syndrome', is an autoimmune disease which can cause abnormal blood clotting in any blood vessel - both arteries and veins.

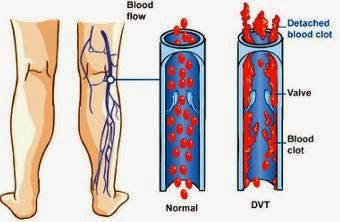

As a result it can cause many different problems. These include clots in the legs known as deep vein thrombosis or DVT, miscarriage and dangerous arterial thrombosis resulting in strokes and heart attacks.

Hughes syndrome accounts for about one in five DVTs and may be to blame in some cases of economy class syndrome, leading to the deaths of young people travelling on long-haul flights. One in five cases of stroke in young people (under 45) is associated with Hughes syndrome. Others are misdiagnosed as having multiple sclerosis because of similar brain symptoms.

Hughes Syndrome also accounts for as many as one in five cases of recurrent miscarriage. Miscarriage is thought to result from disruption of blood flow through the small blood vessels of the placenta. Although the exact sequence of events isn't yet clear (and may vary from woman to woman, pregnancy to pregnancy), without adequate nutrients the placenta fails and the baby is lost. Miscarriage late in pregnancy is very strongly linked to Hughes Syndrome.

The syndrome has also been linked to pre-eclampsia, placental abruption and intra-uterine growth restriction.Unfortunately, some women suffer six or more miscarriages before Hughes syndrome is diagnosed and the appropriate treatment given.

Symptoms Of Hughes Syndrome

There may be a history of sudden problems such as a blood clot or a miscarriage, or a long story of chronic ill health with headaches, tiredness and other illness. People with Hughes syndrome are at greater risk of:

* Venous thrombosis in the legs (DVT), arms and internal organs (kidney, liver, lung, brain, eye)

* Arterial thrombosis, which can lead to recurrent stroke and transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs), neurological problems, and heart attacks.

* Mild thrombocytopenia (low platelet count in the blood)

* Headaches which may be diagnosed as migraines. These may get worse or recur in midlife.

* Multiple sclerosis-like episodes.

* Chorea (abnormal movements)

* Memory loss

* Seizures.

* Heart valve disease Skin rash known as livedo reticularis

* Skin sores and lumps.

* Recurrent pregnancy loss.

Causes And Risk Factors

In Hughes Syndrome the body produces antibodies against phospholipids, a type of phosphorous-containing fat molecule that's found quite normally throughout the body, particularly in the membranes surrounding each cell.

Although Hughes syndrome was first identified in patients with another condition called systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or Lupus) it's now realised that most people with Hughes Syndrome don’t have SLE. However, there does some to be some overlap in a small group of people between Hughes Syndrome and other autoimmune diseases such as SLE or Sjögren’s Syndrome.

People of any age and gender can be affected, although it's more common among women. As the effects of Hughes Syndrome become better understood, it's increasingly thought that as many as one per cent of the population may have some aspect of the condition. As a result it's been described as 'one of the new diseases of the late twentieth century'.

Treatment and recovery

Blood tests are a good guide for diagnosis, but not totally reliable and so are used in combination with the patient's history. A simple blood test is used to detect the antiphospholipid antibodies (also known as anticardiolipin antibodies).

This test is positive in about 80% of cases. Another test, confusingly called a lupus anticoagulant test (it's not a test for Lupus) is also used to help confirm the diagnosis and this is positive in about 30-40% of cases.

Blood tests should also be repeated as harmless antiphospholipid antibodies can be detected in the blood for brief periods (linked to infections and medications for example) giving false positive results for Hughes Syndrome. The Sapporo criteria is a classification method used by researchers, which defines Hughes Syndrome based on a combination of clinical and laboratory criteria.

Treatment is simple and aimed at preventing the formation of clots or thrombus using aspirin or heparin, or both.

Only a low dose of aspirin is needed (75mg a day, which is about one quarter of an adult aspirin tablet).

A woman's chance of carrying a baby to term may be increased from 19 up to 75-80% if aspirin is taken regularly and a heparin injection also given. Heparin doesn't cross the placenta and isn't known to cause any harm to the foetus, although long-term use may be linked to osteoporosis in the mother (newer low molecular weight heparin may cause fewer problems).

Once a thrombosis has occurred, warfarin is usually given. However, this treatment must be monitored and can't be given in pregnancy.

No comments:

Post a Comment